THE DISMISSED FOUNDER

Truth & Reconciliation

Edited by Kiros Auld (Pamunkey/Tauxenent)

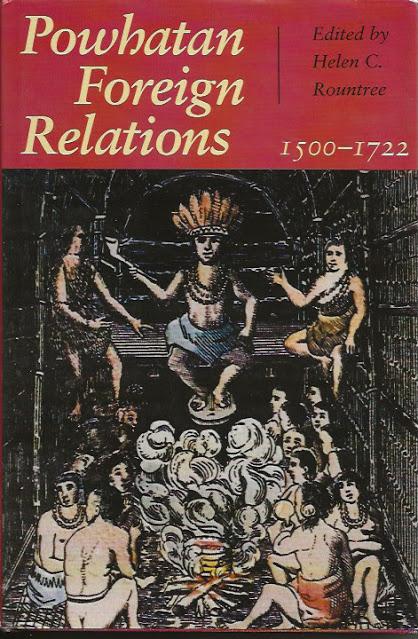

Above: An idealized image of Wahunsenacawh, the Second Powhatan,

a Founding Father and originator of Capitol Hill’s deliberative body from

which we derived the Powhatan Algonquian word and process, a caucus.

Wahunsenacawh, a

six-footer in his 60s, publicly known as Powhatan, in

spite of his fame, is an American enigma. This most dismissed

Amerindian statesman shares the anonymity awarded to today’s Native

American populations and their histories. Ironically, one of his many children

from over 100 ceremonial wives, a minor daughter, Pocahontas, is better

known than North

America’s most powerful 17th century

leader. To better understand the American Government’s adoration for her, they

prominently installed a gigantic painting of her baptism in the Capitol

Rotunda. Afflicted by the Stockholm syndrome and coerced into bigamy, she

achieved the status of virtual Christian sainthood in America’s

pro-accommodationist Eurocentric history. Even less known is one of her brothers,

Taux Powhatan whose mother was a Tauxenent of Fairfax County origin, and one of Washington, DC’s

three historically named tribal nations.

From North Carolina northward, Powhatan II's territory spanned large areas within the state of eastern Virginia. This expansion was less in southern Maryland and included at least the North and Southwest quadrants of District of Columbia, part of his ever expanding northern border on the Cohonkarutan or Potomac River. Yet, some writers today have belatedly sought to either diminish his influence over his domain or include petty kingdoms within his unique political category. His negotiating prowess among highly individualistic Native personas was misunderstood by the English who equated him with a European despot. Inter-ethnic marriage (via warfare?) and trade came with favored status. Pearls, mostly worn by the nobility, came from northern Iroquoian mussels while prized trade copper came from Iroquoians to the South. Siouans to the Piedmont west, were not similarly regarded by the Powhatans. Expansionist Iroquoian and Siouan competition was the norm that had spanned eons. The later demise of the Anacostia River’s Nacotchtank of DC after English contact is evidence of a more violent approach to acquiring trade goods. In this instance it was the highly prized Nochotank beaver pelts which became the envy of English (Jamestown), Algonquian (Patawomeck) and Iroquoian (Susquehannock) speakers.

Truth: Correcting and amending America’s history about its overlooked Amerindian founder.

Reconciliation: Reconcile America’s stepchild treatment towards its indigenous people

In National Native Heritage Month, our city in the District of Columbia needs a South African styled Truth & Reconciliation with its Indigenous descendants.

Wahunsenachaw’s territorial paramountcy

began in Tidewater Virginia

where his mother was born a Pamunkey and his father, Powhatan the First, had

reportedly come from the South to organize a Central American styled eight

nation Algonquian confederation. The Pamunkey, whose spiritually

associated name was the “Place of the Sweat” was a temple city. They were the leading nation in

the chiefdom that became a paramountcy under Wahunsenacawh. Although the

collective Indigenous name for the people that the English

called “Powhatans,” self-identified by descriptively named maternal

tribal origin.

The vast Powhatan territorial influence

began at Tsenacomoco in a territory also called Attan Akamik, meaning “Our

Fertile Country.” Wahunsenacawh is popularly written about by his title,

“Powhatan” or “Dreamer.” He therefore, was Powhatan the Second (Powhatan II)

whose Paramountcy’s domain included five American historical capitals. First

was Tsenacocomoco, second was Jamestown and

Colonial Williamsburg (both during the British colonial era), next was the Seat

of the Confederacy headquartered at Richmond.

And finally in the far northern boundary, our Nation’s Capital of Washington,

DC, reputed as his favorite place to caucus with surrounding Amerindian

nations. Although an Algonquian werowance (leader) of a vast kingdom or

paramountcy, it was chronicled that, for whatever reason, “Powhatan never left

his area” of dominance

Are our children adequately informed about the Amerindian Hemisphere in which they live?

My answer is, NO.

My experiences in the American educational system from the elementary to the

postgraduate levels have formed my view of its collective ignorance about our

hemisphere’s Amerindian histories and locale. Married for 54 years, right out of

Howard University

in 1966, into a Washington Metropolitan Area Powhatan Paramountcy family with

educators and historians, I taught in the Washington,

DC educational systems for 38

years. Throughout my teaching tenure my main concern had been to correct the

benign avoidance of Indigenous Amerindian influences in the forming of our

societies in the Americas.

I began with both my Columbus encountered Caribbean homeland and in my adopted

city of the District of Columbia, which was ironically named after the enigmatic

man who had never set foot here. Thank goodness for National Native American

Heritage Month, which was intended as remedial courses centered on the

Indigenous people of this land. However, the thrust of the month’s original

educational intention, is yet to be realized in 2020. Confusion about

Amerindian histories and cultures abound in their hemisphere which is often

confused as "European” or “African,“ depending on the dominant island or

continental group. North America is envisioned as if it is geographically

located in Europe, while some Caribbean

Islands identify as

culturally African. South and Central America

are identified by their Spanish language and are therefore called

“Hispanic." To underscore the notion of geographic confusion, a large sign

on a Jamestown, Virginia

wall states that "America

is a suburb of Europe."

Popular American history is

unabashedly Eurocentric. Except for the Egyptian styled obelisk, called

the iconic Washington

Monument, our city is

replete with "Egypto-Greek" influenced structures intended as

monuments to power in order to concretize an imported European ethnic

dominance. Our educational institutions have followed suit.

Most

citizens, therefore, have scant information on the Amerindian core

upon which the foundation of the American culture was built. For example,

the Iroquoian “Great Laws of Peace,” a home-grown source

of the US Constitution, formed the foundation of America’s democratic notions that

was once euphemistically ascribed to the distant Greeks. Even

touted “American Individualism" is Native American based, first

emulated and adopted by arriving subjugated English

royalists. The increasing numbers of arriving English indentures were then

free to hunt deer that did not belong to the king, marry Native women

to acquire female-owned land, and go Native. Adapting to and surviving in

an alien Amerindian hemisphere had to be taught to the arriving Spanish

and later English, as exemplified by the latter's

Squanto’s tutelage in corn planting in New England, and

Pocahontas’ lessons on curing tobacco leaves, the Caribbean’s Taino

Amerindian’s sacred weed turned cash crop which financed the American

Revolution.

However, before

the Iroquoian Confederation’s influence on the US

Constitution through Benjamin Franklin and other

contributors from the 13 colonies, there was the Virginia colony's Powhatan Algonquian caucus which left

an indelible mark on the American form of governance. This Algonquian

political structure is still practiced today where it was fathered

by Wahunsennachaw and reborn on Capitol Hill. Not all of the tenants

of Great Laws of Peace were immediately adopted by the US Constitution. Notably

missing from the US

version was the Iroquoian law where "women played an important role in

politics under the Great Law.” In the US Constitution, women's rights came much

later.

The Powhatans were the

"most complex societies, from a sociological perspective, then extant in

the eastern North America” (Rountree). They

were a well travelled cosmopolitan people of the Eastern Woodlands whose

political dominance was recognized by both their indigenous neighbors and the

arriving Europeans. They were admired, envied or feared by whomever they

interacted. There is no question about the dominance of Wahunsenachaw’s

Powhatan Paramountcy over an extremely large expanding territory that was

greater than the size of today’s Maryland and Washington, DC

combined. Wahunsennachaw's governance was not tyrannical nor was it

controlling, but reflected various levels of independence and interdependence

in a geography rife with ethnic competition between the three major linguistic

groups. His gift of persuasion and oratory is exemplified by his recorded speech to Captain John

Smith.

"In the past three decades, anthropologists and historians have become more critical of early colonial sources and less willing to follow their own predecessors’ naming practices without having very good reason to do so” (Rountree).

|

The cover design of a definitive book edited by Dr. Helen Rountree,

anthropologist and historian, who is an expert on the Powhatan Paramountcy. The illustration of Powhatan holding court was recorded by Captain John Smith.

|

Werowance Wahunsenachaw’s Territorial Claim

For the past 401 years, except for the

Powhatan Paramountcy, no other Native American political group in the

Metropolitan DC Area has captured the attention of historians. The importance

of this Native political force is evidenced by the many publications, treatise,

movies, internet & media coverage, locales, personalities, and wars

associated with the Powhatans. No other Amerindian polities in our DC

Metropolitan area have been so studied.

Not so, for her father who was the person responsible for allowing the eventual

creation of the United

States of America on his territory.

Local fame also eludes his succeeding brother, Opechancanough whose

Anglo-Powhatan wars were for America’s first homeland security

efforts. It is not an exaggeration to say that without Wahunsenacawh, there

would be no country called “America."

In the current era of inclusiveness, this is a call for historical truth and

reconciliation with America’s

most downtrodden population whose lives also matter.

Land Acknowledgement

At

least the three countries officially have a Land

Acknowledgement program. In the US, this practice of honoring

Indigenous territory is not yet governmentally instituted. Colonial

confiscated homeland is in the bullseye of history. Some private American

entities have risen to this noble call for acknowledging the specific

Indigenous Amerindian people on whose ancestral territory their structures were

built.

Canada,

Australia and New Zealand, as

well as more and more of private US institutions are coming to grips with the

Truth portion of this honorable proposal. Reconciliation requires more

intestinal fortitude. Reparations is only spoken about as redressing African

enslavement and not that of Amerindians who were the first in that

"peculiar institution.' The truth & reconciliation rationale is based

on addressing the pervasive wrongs of European colonization, annexation of

indigenous territories and lionizing land grabbing “Settlers."

How

is a Powhatan Land Acknowledgement done?

A

DC based Land Acknowledgement video with Rose Powhatan (Pamunkey/Tauxenent)

done for the Sankofa Foundation’s commemoration of

the 55th Anniversary of the Voting Rights Act.

Go to YouTube if video doesn’t pay https://youtu.be/lbntMSQXGiE

RECAP

Where did

he get his political savvy? For these answers, one must look at what was

reported by his people, his title and at least a physical cultural retention,

funerary mound-building for Wahunsenacawh on the Pamunkey Reservation. Was his

male lineage, as some believe, from as far south as the Maya whom we know were

highly sophisticated pyramid builders as well as avid traders and long distant

travelers? The 5,000-year Mound Builders of Ohio with temples on

top, is a Mesoamerican creation similar to the spread of corn, which traveled

along a similar northern route. Was his father's watercraft carried up

from the south by a hurricane in a similar way that early North American dugout

and skin canoes ended up on African and European (from Roman times) shores via

Atlantic storms? Let us entertain this notion here.

Today,

Native American politics has continued to be quite involved and sometimes

contentious. This rewriting trend of traditional boundaries, is also seen

within contemporary Washington, DC’s Native politics. Recently, three family

related Maryland state-recognized

self-identified Iroquoian tribes are making claims on DC and Virginia, sans DNA

evidence of descent from a 1680s extinct Algonquian DC tribe, the genetically

disappeared Nacotchtank of Anacostia. The current expansionists have ignored

the surviving descendants of the two other named historic DC tribes, the

Pamunkey/Pomonkey and the Tauxenant or Dogue who still live in the city and its

Metropolitan Area. The recently organized, politically aggressive Maryland tribes are located 27 miles away from our

city’s borders in Southern Maryland and already have a legal nation to nation

relationship with their own governor's capital in Annapolis. Some of their members are also

making unsupported political claims on the entire 10 squared mile Washington, DC.

The claimants have since extended their indigenous myth into neighboring Northern Virginia’s Powhatan-Tauxenent ancestral

territory. One of their outlandish proclamations also now includes a claim on

part of the state of Delaware.

The Eastern

Woodlands Algonquian leader, Wahunsenachaw, in 1607 claimed at least thirty-odd

nations/tribes in his domain. This assertion was backed up by the identified

nations when later contacted by the English, especially in John Smith’s

account. Added to this easy intertribal access was the geographic layout of the

landscape, dotted by many streams and well travelled rivers which were not

necessarily tribal borders but highways. US Route 1 was an overland highway

which started as an animal trail turned Amerindian travel route, turned wagon

trail. Earlier Spanish ships only mentioned the few “caciques” (leaders) whom

they fleetingly met. The later English camps only knew about those few close-by

nations and other distant ones mentioned by area Amerindians.

The Amerindians of the Powhatan Paramountcy were surrounded by petty chiefdoms.

The cohesive group called Powhatans held sway over an extensive 18,700 to 19,259 square

mile territory from North Carolina, Virginia,

Maryland, to Washington, DC, which included over 32-34 Algonquian nations.

Politically labeled as a kingdom by the English royalists, called a

“chiefdom" by detractors, the werowance and weroansqua (male and female

leaders) governed by a democratic deliberative styled caucus.

|

|

|

Pawahaatuun, A Maya sculpture in

Copan, Mexico of the Ancient One, a god within the Maya pantheon who held up

the four corners of the world.

|

Wahunsenacawh was the son of the

first Powhatan, an arriving “dreamer” who began North

America’s first Amerindian group of nations under the leadership

of one person. This governmental entity had the earmarks of an empire or a

kingdom, which is a group of nations ruled over by an individual.

This description fits Powhatan the First since he had come from the south where

there were city states and empires, His title, "Powhatan,” has a

Mayan concept in their Pawahaatuun, who was associated with

the calendar god who positioned himself at the four corners of the sky,

holding up the world.

Whatever is believed, the facts of our

Amerindian foundation is an indisputable historical reality not widely

promoted. This overlooked segment of our nation's history perpetuates the

unrealistic myth of a European based entitlement which is daily played out in

our National discourse.